The Shimano Archive

嶋野 栄道 老師 アーカイブ

http://www.shimanoarchive.comZen and the Art of Seduction

(This article/exposé was never published by The Village Voice in 1982, allegedly due to fears of legal retaliation.)

Robert Baker Aitken Rōshi Archives.

By Robin Westen

Leaning against the couch, my host loosened the belt of his flowing white robe, patted his stomach, and smiled. He had the most incredible radiance in his eyes. “Have you seen the temple in our New York Zendo?” he whispered. “Come.”

I was seated across from him on a small round cushion. My legs were numb–a dead giveaway, I suspected, that I had only been practicing Zen for a year.

He stood and held out his hand.

I took it awkwardly, but before I could get the feeling back in my legs, he ripped me off the floor and pulled my body against his, then grabbed my breast, prodded my mouth with his tongue, and started to pull up my skirt and reach between my legs.

For a moment, I was too stunned to react. But then I pushed him away, and stood there, my arms distancing us. I looked straight at him. He stared right back. He acted as though nothing had happened. He was still smiling.

I was sickened, frightened, disoriented, confused. The physical assault was bad enough, but even worse was the emotional betrayal. He was my Zen master, my teacher, my guide, and he had brutally violated my trust.

I didn’t know what to do next, so I just followed him down the stairs to the temple where I watched him bow to the Buddha. Then I saw the red light above the exit sign and quickly left the building.

When I stood outside on the street, I was still shaken. I had not only been sexually attacked, but the offender was one of the most respected spiritual leaders in the Zen Buddhist community, the leader of the New York Zendo, Eido Shimano Roshi.

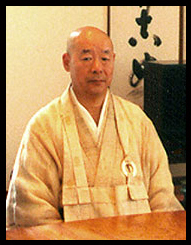

Eido Shimano

Could I have been an isolated incident? I doubted it. I began my investigation that afternoon, with the first of over 50 phone calls I would make to past and present students. During the months of interviewing, I discovered that Eido Roshi had seduced, or attempted to seduce, dozens of women while acting as their spiritual guide. At least three of the women, as a result of their sexual-spiritual relationship with Eido, had suffered mental breakdowns serious enough to cause hospitalization.

I was to learn that Eido had been involved in sex scandals for over 15 years, but each time they were brought to light in the Zen community they were silenced. I was also to learn, through an open letter written to the Board of Trustees of the Zen Studies Society by its former president, that Eido had apparently neglected to pay any personal income taxes, was accepting donations to the society from a convicted drug felon, and had been abusive to his own 75-year-old Zen Master, Soen Roshi.

When I questioned Eido about these accusations during telephone conversations, he denied them all.

I met Eido Roshi at Dai Bosatsu, the Zen monastery in the Catskills where he is abbot. This particular morning was the last day of sesshin, the seven-day silent retreat, during which participants (the sangha) sit in lotus or half lotus position for almost 14 consecutive hours. Unbearable is in no way an accurate description of the pain. It can be transcendental.

The day had begun as usual at 4:30 a.m. Three hours later, after morning service, chanting, and bowing, followed by one and a half hours of meditation, breakfast was being served. I sat staring at the bowl of oatmeal which suddenly appeared beautiful, quintessentially beautiful. I had not realized that oatmeal was so–so beige, so utterly beige. It occurred to me that each grain was–unique yet the same. I was filled with excitement. I no longer felt pain. I began sobbing. Then I remembered, and controlled myself, breathing deeply; the first rule of sesshin is the maintenance of silence.

Later that morning I was running along the dark hall of the zendo to the dokusan or guidance room to see Eido Roshi. Despite my eagerness, I made sure to enter with the proper Zen etiquette, bowing once at the door and once directly in front of him on my knees. The room was pitch dark– except for a nightlight silhouetting Eido Roshi’s shaved head. His body was clothed in meticulously draped black robes. Hs exceptionally small, perfectly formed feet were just visible beneath his robes. He fixed his eyes on me, until I understood that this was meant as an invitation to speak. I tried to control my excitement as I told him my experience with the oatmeal. He watched me for several minutes in silence, and then delivered his judgment. “What you have described is kensho. Enlightenment.” He cupped my head in his hands and held it against his chest.

That evening, at the onset of the final period of meditation, Eido Roshi announced that one member of the sangha had experienced enlightenment on this, the last day of sesshin. From the other seated students there was no acknowledgement, no response of any kind. In Zen, the watchword is “detachment.” But he was fixing me with that expressionless and serene gaze of his, and he had all my attention. I waited for a sign. It came. He bowed in my direction.

Two hours later, Sesshin was over. I was on the point of leaving the monastery when Eido approached me and invited me to take tea with him at the Zen Studies Society in New York City.

I was again sitting in half-lotus. This time I was nervous. Okay, so I was enlightened, but instead of feeling elated, I had been depressed all week. Nothing had really changed.

Now I was having tea with Eido Roshi. I was prepared to talk about my spiritual development, but surprisingly all he said was, “The best time to make love to a woman is right after sesshin, when she looks her sexiest. If I had my way, if people understood the essence of detachment, everyone would sleep with each other the night sesshin ends.”

I thought he might be flirting, but Zen is so enigmatic. In fact, Zen is filled with so many apparently ridiculous questions like “What is Buddha?” Ridiculous, because an acceptable answer is “Shit stick.” Well, I thought, behind Eido Roshi’s words deeper meanings must lie.

But then Eido attacked me and it all collapsed. I had come for spiritual guidance, but instead I was being seduced. If the oatmeal was enlightenment, was this Zen Buddhism?

Approximately half a million Americans are practicing some form of Buddhism and tens of thousands are Zen practitioners. Unlike fly-by-night cults with gurus coming out of the woodwork, Zen has had a slow but enduring growth, with an unblemished reputation. The media has treated it gingerly, if not favorably. Within the last six years, one feature on Eido Shimano Roshi and one on Zen’s place in America have appeared as cover stories in The New York Times Magazine.

Buddhism began to develop in Japan in the 12th century, and was introduced into America in the first years of the 20th century by a wandering Japanese monk. By the 1950’s the Beat Generation had taken it up. In the ‘60s it had entered the consciousness of the American upper-middle classes through the stories of J.D. Salinger and the art movement Minimalism.

Probably Zen’s appeal has never been better expressed than by D.T. Suzuki in his book, Is Zen Religion? “It is not a religion in the sense that the term is popularly understood. For there is in Zen no God to worship, no ceremonial rites to observe, no future abode where the dead are destined to, and last of all, no soul whose welfare is to be looked after by somebody else.”

Zen is not based on “speculative philosophy,” but on actual experience of ultimate reality. Its followers don’t believe in “Supreme Being,” they merely strive for Nirvana, Great Void, Non-Being. Unlike the Catholic Church, there is no hierarchy, no father figure to look over individual temples or Zen masters. There is no governing body to enforce rules, for in Zen there are no rules. In fact, there’s almost a total disregard of formalism.

The only figure of authority is the Roshi, or teacher, and his most important job is to help students gain enlightenment. In this position, he can exercise incredible control over his disciples’ psyche, especially in the dokusan room. After sitting for several hours in meditation, the mind is open to any possibility, and often there is an altered state of consciousness. The roshi can easily use his position to persuade or coerce a susceptible student, similar to a psychiatrist’s control over a vulnerable patient. Even more powerful is the roshi, for like a priest he can sanctify marriage, perform last rites, and offer spiritual guidance to families and individuals in trouble.

In the United States, there are only a handful of roshis, but who they are is a mystery. Reportedly, there are two official listings in Japan, but the roshi bookkeeping, in the tradition of Zen, is informal. And once a Roshi, almost always a Roshi. In Japan’s past, when monks had strong provocation to oust their teacher, they no longer fed him. In the United States, it’s another story.

Eido Roshi lives well. The New York Zendo is housed in the same facility as the New York Zen Studies Society, 223 East 67th Street, a lavishly converted four story carriage house on the Upper East Side, with more than ample room for Eido’s residence. However, Eido and his wife Aiho lived two blocks away, in their own well-appointed townhouse at 356 East 69th Street. The day I was to have tea with the Roshi, I had to wait — he was in the middle of his daily afternoon shiatsu massage.

Eido can thank his followers for his opulent life style. Many of his sangha are, in fact, highly educated and affluent men and women. Men like William P. Johnstone, a former executive of Bethlehem Steel Corporation, who was the treasurer of the Zen Studies Society; like George Zournas, publisher of Theatre Arts Books, who is president, as was the late Chester Carlson, inventor of the Xerox process, who donated $3 million for the purchase of land for the Catskill monastery, Dai Bosatsu; like author Peter Matthiessen (now a Zen monk himself but with a group in Riverdale), who played a crucial role in securing a $75,000 personal donation from Lawrence Rockefeller and annual contributions of $10,000 from the Rockefeller Foundation, like blues singer Libby Holman, who became a Reynolds tobacco heiress; and Mitchell Rosset, a former publisher, with her husband Barney, of Grove Press. Eido can thank his followers – whether he’s living at the New York Zendo or his private townhouse, or at Dai Bosatsu Zendo, whether he’s traveling to Europe, the Far East, Japan, or the West Coast–for he’s doing it in style.

Dai Bosatsu Zendo is a classical Japanese temple majestically situated on 1400 acres in the small town of Livingston Manor in the Catskills. You arrive at DBZ after driving along route 17 with billboards reading “Brown’s,” “Concord,” “Kutshers”–the heart of the Borscht Belt. Once exiting off 96, it’s about 20 miles to the monastery. Formerly the estate of Harriet Beecher Stowe, the impressive 26,000-square-foot structure overlooks an equally impressive 30-acre lake.

Dai Bosatsu is the largest and most authentic Zen temple outside Japan. The monastery has all the necessary features for traditional Zen practice–a hall for meditation (Zazen Hall), a hall for ceremonies, lectures, and chanting (Dharma Hall); rooms for rest and study, a ceremonial tea room, a dokusan or guidance room, a traditional Japanese dining room with low tables and cushions on the floor, an enclosed courtyard; a formal entry; and a reception area with an altar and an extremely valuable antique Buddha statue.

There are bells and gongs worth more than tens of thousands of dollars each, and one enormous gong, smelted in Japan, valued at over $100,000. There are also hand-pegged oak floors, 15 decorative windows shaped like candle flames, and three hot tubs, three and a half feet deep. Not to forget a library, large kitchen, offices, meeting room, food storage facilities, and woodworking shop, as well as a wing with private quarters for Eido Roshi.

Eido came to America in 1961 at the age of 29, a young monk sent by his teacher Soen Roshi to act as an interpreter for Yasutani Roshi, who was lecturing and holding sesshins in the United States. In 1963, Soen sent Eido here permanently. His first stop was Hawaii, where he was to serve as monk-in-residence at the Ko-An Zendo in Honolulu.

Although it was never publicly acknowledged before, Robert Aitken, head of the Ko-An Zendo, told me during a telephone conversation that Eido’s three year term was filled with “scandal and tragedy ending in éclat.”

Aitken explained: “I discovered Eido’s sexual involvements by accident. Two women in our group had nervous breakdowns. One of them attempted suicide. It was through their psychiatrist that I first got wind of anything. I had consulted with their doctors because I wanted to better understand mental illness so that I could in some way help these women. That’s when I learned of their relationship with Eido. His departure in 1964 from Hawaii was directly linked to the fact that these women were sexually involved with their Zen teacher, Eido Roshi, and had become mentally ill as a result.”

Eido insists in his autobiographical notes in his book Namu Dai Bosa, published by Theatre Arts Books in 1976, that he left Hawaii because “The Hawaiian climate was too good. It was a place for vacationers or retired people, but not for Zen practice.” (Aitken maintains that despite the glorious weather, Zen in Hawaii is flourishing.)

According to his autobiographical account he arrived in New York on December 31. He had virtually no money and no place to stay. However, there was a note for him at the airport from an American couple he had met in Honolulu. the note read: “Sorry we can’t meet you. But come straight to our apartment.” He remained at his friend’s apartment until he was found a sublet on 85th street off Central Park West.

His only possessions were a standing Buddha and a keisaku (a wooden stick sometimes used during Zen meditation to strike the student between the shoulder blades). He had no furniture, no tea bowls, no incense burner, not even the all-important round, floor cushions. Yet he began holding classes–it was the ‘60s and many people were ripe for Eastern teachings. At the time Eido was the only accessible Zen master in New York City, and before long word of mouth spread that he was a charismatic master with a certain ineffable presence. New Yorkers began to arrive at his door–so many, in fact, that on certain nights people had to be turned away. Students brought cushions, blankets, tea bowls, donations–all the accoutrements. Enrollment rose and multiplied. After the lease on the sublet ran out, Eido moved to a ground-floor office space four blocks away.

Two of Eido’s first New York students speak of him with warmth and admiration. Ruth Lilianthal, a student for 15 years: “I knew Eido Roshi many years ago and he was doing phenomenal work. I’m very grateful to him, as are so many others–for training that would not otherwise have come our way. There is no doubt that he is unique.”

And Randy Place, a disc jockey and newscaster with station WKHK and a Zen enthusiast: “I can only say I owe Eido Roshi so very much. In every way, he is a remarkable man.”

The ground floor soon became inadequate for both the numbers and the quality of well-heeled students Eido was attracting. In 1968, a socially prominent couple who wished to remain anonymous donated the money to purchase and remodel the four story carriage house on East 67th Street. In 1971, the Catskill monastery site was chosen and the donation of $3 million from Xerox’s Carlson made the purchase possible.

“Eido Roshi’s fund-raising abilities were incredible,” says Peter Gambi, a Wall Street investor and former student. “Whatever he wanted he would get. He has that kind of ability to make you think that if you don’t pour all your money into his projects or into Zen practice, then you are making a big mistake. He’s very talented that way.”

In September 1971, Soen Roshi ordained Eido a roshi. There was a lavish ceremony with hundreds of New York followers in attendance. Usually a monk remains in a monastery between 10 and 15 years, but the United States was developing a thirst for zen, and a Roshi was needed in a hurry. Soen couldn’t leave Japan, so the young Eido took his place.

In only a few years, Eido Roshi had charismatically or “karmically” nurtured Zen in America in thousands of New Yorkers and has made a cushy home for it in the city. But the Zendo home was not a happy one.

Amid the splendor of Dai Bosatsu in 1975 the biggest sex scandal broke. One woman, who had been Eido’s mistress for years, confided to another woman, only to discover that she was not the only one. Together they began to make telephone calls and soon learned that there were at least half a dozen other female members

Former student, Adam Fisher, a writer living in New York City refers to that period as "Fuck Follies I.” (“Fuck Follies II" took place on a smaller scale during the later period of 1979.)

As their internal inquiries mounted, another half a dozen women admitted that Eido had made advances to them while they were attending sesshins, and that he had used the dokusan room as his station for seduction.

One such woman was

, who now lives in San Francisco. In a letter to another Eido student she stated, “I experienced quite a bit of harassment from Eido Roshi, from innuendo to proposition, during my stays at Dai Bosatsu. The first time it was just a barrage, in dokusan during sesshin. For six months I never spoke a word of it. I vigorously denied it to board members of the Zen Studies Society. But after I left, I found out Eido Roshi had propositioned other female students. We had been close friends and yet we had kept silence on something that was disturbing us every day in order to protect the group, the Roshi. Women who had affairs with Eido had taken painful falls when he tired of them.”

, who now lives in San Francisco. In a letter to another Eido student she stated, “I experienced quite a bit of harassment from Eido Roshi, from innuendo to proposition, during my stays at Dai Bosatsu. The first time it was just a barrage, in dokusan during sesshin. For six months I never spoke a word of it. I vigorously denied it to board members of the Zen Studies Society. But after I left, I found out Eido Roshi had propositioned other female students. We had been close friends and yet we had kept silence on something that was disturbing us every day in order to protect the group, the Roshi. Women who had affairs with Eido had taken painful falls when he tired of them.”

Another woman,

, a former student of Eido’s, now a housewife and mother of two children in Florida, explains: “During sesshin he gave me a book to read. It had seven chapters, and of course sesshin is seven days. So every evening I would go downstairs to the nun’s quarters–there was decent light there–and read a chapter. On the seventh night, Eido Roshi appeared in the room. He asked me what I was doing and I said: “It’s the seventh day and I’m on the seventh chapter.” He stared at me for a moment or two and then he told me to follow him. I thought to myself: “This is great. Now I’m going to be initiated!” And I followed him upstairs to his quarters. I started to tell him about my spiritual experiences and he told me to be quiet.

, a former student of Eido’s, now a housewife and mother of two children in Florida, explains: “During sesshin he gave me a book to read. It had seven chapters, and of course sesshin is seven days. So every evening I would go downstairs to the nun’s quarters–there was decent light there–and read a chapter. On the seventh night, Eido Roshi appeared in the room. He asked me what I was doing and I said: “It’s the seventh day and I’m on the seventh chapter.” He stared at me for a moment or two and then he told me to follow him. I thought to myself: “This is great. Now I’m going to be initiated!” And I followed him upstairs to his quarters. I started to tell him about my spiritual experiences and he told me to be quiet.

“Sssssh…ssh…be quiet!” he said in a whisper.

“And almost before I knew it, he had pulled off his robe and was laying down on the bed stark naked. Well, I was in such a state then, I thought this must be some sort of test of detachment. It sounds ridiculous now, but when you’re serious about your Zen practice, and when you have a lot of respect for someone, you think the best, no matter what. And I thought the best when he ordered me to go down on him and perform fellatio. He told me it would be a spiritual experience for me… it wasn’t. To tell the truth it wasn’t much of a sexual experience. I don’t know why, I guess I was trying too hard to be detached. Anyway he knew that I didn’t enjoy it and after that he just lost interest in me.”

Another personal experience was spoken about by a woman I’ll call Barbara Shuster, who is now married to a plumber and former Zen student. “When I first started Zen,” she told me, “I thought I was a lesbian. I’ve always thought of myself as the homely type and I was attracted to other women who were better looking than me… Anyway, the first time I went into the dokusan room and confided this to Eido Roshi, he looked at me in that way he does… and then he said: ‘Oh…is that sooooooo… And then finally he said: ‘Wellllll… there’s only one way to find out…’ He stared at me for the longest time and then he said he had a present for me. I should see him later.

That evening I went to meet him. He opened up a box on the floor and brought out this beautiful silk scarf. He told me it was for me it was my present, but he just sat and fondled it on his lap. Well, I was sitting across from him. I felt relaxed. My legs were apart in lotus position and I was watching him fondle this silk scarf, and he never said anything, and the next thing I knew his hand wasn’t fondling the scarf, it was up my skirt. I screamed at him: ‘Eido Roshi! What are you doing. What do you think you’re doing?’ He took his hand away and all he would say was, ‘What do you mean? I wasn’t doing anything. What did you think I was doing?’ And that was the end of it for me. Like you don’t make a mistake like that. I know what he was doing, so why didn’t he admit it?”

As peculiar as “Barbara’s” story sounded, I had reason to understand. At the beginning of my investigation, I had sent a letter to Eido reporting my intention to write an article about our incident at the New York Zen Studies Society. When he received it, he phoned me at my office at ABC Television.

“You have your viewpoint,” Eido said. “Other people have their viewpoint. You cannot write except by your own viewpoint.”

I agreed with him.

“That’s why I at least want to say what is my viewpoint so when you write you can see it from different angles,” he continued. “The first thing I want to say is about what you mentioned you experienced in the dokusan room, and your personal feelings at the time. Do you remember what happened?”

I assured him I did. Perfectly.

Eido said, “I was really in a sense surprised when you held my hand and put it on your chest.”

“What!” I was furious.

“Cheek. Chhh––eeeekk.” Eido corrected himself.

Then I corrected him. “That’s not exactly what happened. You told me to come closer in the dokusan room. Then you took my hand…”

Eido interrupted, “Yes, and then you placed it on your ch–eeek.”

It was getting silly. “I placed my own hand, on my own cheek?”

“No, No. You took my hand and placed it on your cheek.”

“Well,” I said, “that just never happened.”

Eido continued, despite my objections. “And you said to me, ‘I want to stay like this forever.’”

“That just never happened.” I said. “I have an entirely different perception of what took place.”

“This is exactly the problem you see.” Eido said. “What you remember and what I remember are entirely different. Nobody was witnessing, so you can say it your own way, and I can say it my own way. That’s really the problem. What you will write will be from your point of view. Your subjective reality.”

I reminded him that I had interviewed lots of women, to which he responded, “let’s put that aside for a while.”

“All right. But what about when I came for tea?” I asked.

“Yes, I also have my own way of perceiving that.”

A very different story came from a woman I’ll call Rona Stuart, who runs a typing service in New York City. Rona said: “I take responsibility for initiating sexual relations with Eido Roshi. It started in 1972. I was his secretary, I helped him. I was everything to him. I was his confidante. He told me everything–everything. When I discovered what was going on, I was completely shattered. He had been everything to me–father, lover, guru–and I thought I was indispensable to him too. When I discovered the truth, I broke down. I had to spend some time in Payne Whitney. But maybe the hardest part of all was that after I broke down, I simply ceased to exist for Eido. Can you understand that? He ignored me completely. And I had been at his side for five years. But do you know something–I forgive him for that too. Because I think he’s a sick man. He’s the sick one, not me.”

A major Zen event was scheduled for July 4, 1976, to coincide with the bicentennial celebration. It was the official opening for Dai Bosatsu. All the Roshis and spiritual figures in the country were invited to attend the ceremony. But one student, Nora Safran, was so fed up with “Eido’s screwing around with the sangha,” as she puts it, that she sent a letter to all those who were invited, telling of Eido’s sexual appetite during sesshin, how he used his position to seduce female members, about his manipulations and lies. She urged them not to come as a protest.

But on the day of the dedication, every Roshi was there except for Soen, Eido’s own teacher, who was conspicuously missing. He had remained in Japan. Members of the sangha say that Soen, possibly as a result of Nora’s letter, was quietly protesting his disciple’s behavior and publicly dissociating himself from Eido.

Nora explained to me, “Many of the followers from Dai Bosatsu spoke individually to the various Roshis who attended and told them again, privately, about Eido. Still, the Roshis kept silent, to save face, to save Zen in America!

“I did learn that Soen had later spoken to Eido’s wife, Aiho. She was told about her husband’s seductions in front of several of the sangha, and Soen asked his wife to keep him under control. Little did Soen realize that Eido’s sexual appetite would increase as his power to manipulate his followers increased.”

Fed up with Eido’s activities and the apparent apathy of the other Zen masters, Nora started her own zendo in a loft in Chelsea. About 25 members defected to the alternative center, some to other Zen Groups in the city, and others dropped out of the practice completely.

To the outside world, Eido Roshi remained and influential figure, his reputation unmarred. In a few months, the New York Zendo, emptied of half of its members, resumed normal operations, and enrollment began to increase once again. In 1977 The New York Times Magazine published its cover piece on Eido and Dai Bosatsu. In a short time, the Zendo was once again filled to capacity.

Nora explained why Eido’s activities were not publicized. “When this thing was first brought out in the open among us, I was as hotheaded a revolutionary as anyone, I wanted to picket the place, expose him in The Village Voice, or maybe something classier than that. But I didn’t do any of it. Don’t get me wrong, the fact is I think the sex thing is just the tip of the iceberg. I suspect he’s crazy, truly crazy. I’ve seen him manipulate people in every possible way–sex is just one. But on the other hand, he’s not like some swami or something where they’re having scandals every five minutes. Zen Buddhism is very, very respectable. This is so unheard off. This guy is such an oddball in the Zen establishment. If we let outsiders know about Eido, it would be the end. Why ruin Zen in America?

While cleaning the dormitory rooms of the Catskill monastery, a monk discovered the diaries of a woman I’ll call Laurel Sloane. She had left the monastery in a hurry. The diaries explicitly described her encounters with Eido.

and others asked her to bring the diaries to the attention of the board of trustees of the Zen Studies Society. She agreed, a storm ensued, but shortly afterward the commotion was calmed. The force behind the cover-up was Sylvan Busch, then vice-president of the Zen Studies Society, and now president. He has been with Eido for over 15 years.

and others asked her to bring the diaries to the attention of the board of trustees of the Zen Studies Society. She agreed, a storm ensued, but shortly afterward the commotion was calmed. The force behind the cover-up was Sylvan Busch, then vice-president of the Zen Studies Society, and now president. He has been with Eido for over 15 years.

In 1980, it was reported by a woman who regularly attends sesshins at DBZ that Eido had become romantically involved with a female monk named  . A former student, who asked to remain anonymous, said, “I don’t know what he could have done to

. A former student, who asked to remain anonymous, said, “I don’t know what he could have done to  in just two years. When she first came to DBZ, she was really attractive and vibrant. She had a terrific smile and lots of enthusiasm. I remember thinking her red hair was fabulous. Of course, she shaved her head, but after her affair with Eido it grew back thin and gray. Her teeth looked rotted and her face drawn and lifeless as thought she had aged 20 years.”

in just two years. When she first came to DBZ, she was really attractive and vibrant. She had a terrific smile and lots of enthusiasm. I remember thinking her red hair was fabulous. Of course, she shaved her head, but after her affair with Eido it grew back thin and gray. Her teeth looked rotted and her face drawn and lifeless as thought she had aged 20 years.”

Norman Hoeberg, Zenji or teacher of the Washington, D.C. Zendo ( a satellite of the New York Zendo). explained how the situation appears from the Zen master’s point of view. Six feet four, and by his own admission somewhat lacking in physical grace, Norman almost filled my small office when he came to talk about Eido.

“He is my teacher and my Zen master,” he began in a rush. “I am his student and his disciple. And all of these stories… well, because of what he is and of what I am, I must give him leeway in the dokusan room. But I will admit, I don’t know where his head is at. He is a mystery to me. Really a mystery. From your point of view he’s seduced and destroyed women. But he’s also destroyed men, not through sexual manipulation but by power manipulation. I heard him arguing very loudly with a young man once. And then the young man went off and killed himself.

“In his presence a woman fears physical rape–maybe. A man is spiritually raped with subtle mind control. But, you know, when a woman comes to see me in my dokusan room, and it’s dark and quiet, and you know for certain that no one will come to interrupt you–and all that makes for intimacy. And this woman, she might be feeling desperate about her private life, about her marriage, maybe, or about her boyfriend–or not having a boyfriend–or whatever. And she’s come to me for answers. It’s like being asked to play God. She’s come to me for spiritual guidance, and you want to know how I feel? I feel a sense of vulnerability about her. It’s like an atmosphere you can almost take hold of. And you look at this woman across the floor from you and what she’s brought with her–and it’s like a presence between you–and I tell you, you want to push it aside, and if you’re not careful, you can find yourself taking advantage of her.

Maureen Friedgood, president of the Cambridge Buddhist Association and a one-time student of Eido’s, shared none of Norman’s empathy. “It seems Eido has a terrible problem. I tried hard to defend him all these years because in many ways he’s such a gifted teacher. I hoped he would outgrow this. But he’s still behaving like an adolescent boy. He just can’t resist.

Maureen Friedgood remained loyal for over 20 years but now she refuses to go back and warns her students about Eido’s conduct. “It’s just dreadful,” she said. “I and many people feel Soen Roshi should have recalled Eido to Japan and sent somebody to take his place. It’s very upsetting and very bad for Zen in America.”

I had heard, during my interviews, that Soen Roshi was returning to the United States for the first time in seven years. I sent a certified letter to both the New York City Zendo and Dai Bosatsu. I described the incident that had taken place with Eido at the New York Zendo, and the numerous interviews with other women who had experienced similar situations.

One week later, I received a call from Soen Roshi, who was at Dai Bosatsu. We agreed to meet in a few days at the Catskill monastery. I had reason to change our appointment, and when I phoned back my call was intercepted by Mark Uretsky, the office manager. “The situation is this,” he said. “Soen Roshi is not available. In order to be reached, he has to be reached through Eido Roshi, who is in New York City, but will be returning in two days [the very day Soen and I had scheduled our meeting]. The way we’re working it now is that I’ll leave a note with Eido Roshi describing your interest in speaking with Soen Roshi.”

I asked it he would also leave a note for Soen to let him know I had called.

“Soen Roshi is not available,” he repeated. “He’s only available through Eido Roshi.”

I asked if Soen was aware of this new procedure.

“Whether he’s aware of it or not is not really essential.” Mark said. “The essential fact is–if you want to reach Soen Roshi, you have to go through Eido Roshi.”

Mark told me that I should consider the fact that Soen is an old man, 75, not in the best of health, in America for the first time in many years. “Just consider these facts and then reflect on whether you’re doing, or rather Eido Roshi’s doing the right thing.”

I phoned the next day and tried again. This time I spoke with Kana, a monk who was ordained during the same sesshin I attended. Kana told me that the reason Soen Roshi was unable to speak to people was that he was no longer capable of making arrangements. He was “forgetful” and would tend to make several appointments for the same time. Or forget that he had one. “If you’ve made an appointment, don’t expect him to be here necessarily.” Kana was clearly insinuating that Soen Roshi was senile. Yet no one else I interviewed suggested that Soen had any mental problems.

Soen Roshi was the only man with the power to oust Eido, the only man with the power to send him back to Japan. It was not surprising that Eido seemed to have virtually imprisoned his own teacher–his own Zen master.

I decided to try to keep the date I had made with Soen Roshi. Before I reached the gate of Dai Bosatsu, I thought it likely I would be barred; I was not. I parked my car in front of the Monastery entrance. To my surprise, the door was open. I took off my shoes, climbed the stairs, and looked around. The monastery seemed to be inhabited by silence. I walked slowly toward the tea room. On the threshold, I paused, looked in, and saw a frail, elderly man, dressed in a peach colored robe, with a sleepy-looking face, but with lucid and alert eyes. I entered and bowed respectfully. He returned my bow. and reached

Soen suggested we share tea before beginning our discussion. An elaborate tea setting had already been prepared, and I watched silently as he whipped the green tea, steeped it, and then poured it into ceramic cups. He spoke about the origin of the tea and the little baked delicacies, also brought with him from his native country. Finally, Soen looked up from his tea and said, “We must begin now. This is a very serious matter.”

I took out my notes and tapes and spread them across the low table. I spoke softly. I told him about my experience in the dokusan room during sesshin. I told him how Eido insisted I had kensho. I told him about the follow-up attack at the New York Zendo. I explained that when I confronted Eido on the telephone about these events, and about the other women who said they shared similar experiences, Eido’s response was, “Don’t speak about them. They were different. You are the only one who has experienced kensho.”

Soen fixed me with his eyes and we sat staring at each other. Silence returned to the monastery. Finally he spoke: “This is a grave matter. Very grave. I showed Eido the letter you sent here last week. I asked him for an explanation. He gave me one, but it was not satisfactory. He is a liar.”

Again we stared at each other in silence. It was Soen Roshi who broke it.

“Somehow Eido has left. He must still not have an answer.”

I looked hard at Soen, trying to fathom him. I failed. His gaze was impenetrable.

When he spoke again his lips scarcely moved. “This problem happened almost seven years ago when Dai Boastsu was to officially open. Now it is happening again. The responsibility is clearly mine.” He paused again. “It is a grave matter.”

I reminded him that in my letter I had asked for a “turning word.” (In Zen, a “turning word” is the essential factor that will alter a situation.)

He seemed surprised. “today?” But he did promise to have one for me on the following day. He said he needed to consult with George Zournas, president of the Zen Studies Society, an old and respected friend.

That evening I had a long telephone conversation with George. “Well, in the whole history of Zen,” he said, “there have been those outrageous monks who do things that are very difficult for people to understand. My position through out all this is that I’m in no position to judge. At Theatre Arts Books, we publish Stanislavsky. And when things like this were brought to him, he said, “You know, I have so much to do, working on my own character, that I don’t feel I can judge anyone else.

“The fact is, it may appear that some people have been injured by him, but to balance this, many have nicely benefited. For myself, I just don’t choose to play God and balance things out. There’s these 50 pounds to advantage and these 60 pounds to disadvantage, so he’s 10 pounds in the red! I think when we begin judging other people in this area, we are treading on dangerous ground. Because none of us know really what’s in the mind of any of us involved in this.

Maybe in his lifetime, maybe in the next, there will be certain consequences he will endure.”

The following week George Zournas, president of the Zen Studies Society for 15 years, resigned.

The next morning the phone rang. I was certain it was Soen Roshi with the “turning word.” But it was David Schnyer, resident director of Dai Bosatsu, Eido’s right-hand monk and member of the board of trustees. David told me he was acting as Soen Roshi’s secretary. He said that any further communication at this time would be best dealt with through their lawyer. “Soen,” he said, “is requesting that you do not call again.”

David insisted again and again that these were Soen’s own words. But according to Frank Locicero, a tax auditor at the Internal Revenue Service and a board member of the Zen Studies Society, David was merely following Eido’s orders. Frank had heard of my investigation from George, and called to help me a week after my talk with David. “David Schnyer is lying,” he said. “It’s just more manipulation by Eido. David probably doesn’t even know the truth about what’s going on.”

Frank was the first to volunteer aggressively to help expose Eido–publicly. He promised to give me a copy of a letter written to the board by George Zournas, with Zournas’s permission.

The following is an excerpt: “Until her resignation in the wake of Eido Roshi’s 1975 sex scandals, one of the most active Trustees of the Society was Margot Wilkie. She is from the world of the trustees of the great charitable foundations of Asia Society and such. Our friendship continues and at her dinner parties I meet many of these powerful people–some of whom have contributed to our work in the past. When I am introduced as President of the Zen Studies Society and the connection with Dai Bosatsu and Eido Roshi is established, we are regaled with such remarks as, ‘How is the horny old pasha and his harem up there in the mountains?’ Or, ‘Boy, is that the kind of spiritual exercise I’d like to be doing.’ Of course such people have no intention of making contributions to support such activity. We have applied to some of the foundations these people control for additional grants–their reply is that their interest has shifted to other areas–they have nothing for us.

“This has become so serious that for the last ten years the Society has been running on money contributed to us by a convicted felon. We have been functioning on money that he obtained from selling illegal drugs!”

“For many years various members of the Board have protested the fact that Aiho, Eido’s wife, was also Treasurer of the society. They found this totally unacceptable, but Sylvan Busch and I were able to quiet their complaints. But this question is made even more serious by Sylvan’s statement that for many years the Shimanos [Eido’s legal surname] did not file income tax reports. Why? If this is true, this is one more example of the Buddha Dharma and the Society displayed by the Chairman of the Board and its Treasurer. Had such a story reached the newspapers it would really have finished us off.”

In light of my investigation, old and new ghosts had come haunt and some of the trustees were planning to perform an exorcism: they were going to request Eido Roshi’s resignation. Leading the dissidents was George Zournas.

Eido had made some serious strategic errors. First, he had attempted to oust Peggy Crawford from the board. Peggy had been Eido’s dedicated secretary for over 12 years. She had donated tens of thousands of dollars, chauffeured him regularly to the Catskills, and was one of the few members of the Zen Studies Society I had spoken to who had supported him without exception. She had even suggested that Eido’s attack was my fault. “You would do well to join EST and learn not to judge,” she suggested. But Peggy recently requested permission to sit sesshin with another Zen master. This is not unusual–students often go from one Zen teacher to another to satisfy their inquiring minds–yet Eido’s ego was hurt, or he was becoming paranoid. He sent Peggy a letter, circulating copies to other members. “Since you are now sitting elsewhere and due to your lack of support,” it read in part, “it is inappropriate for you to continue to sit on the Board of Trustees of the Zen Studies Society.” After Peggy spoke to the society’s lawyer, and Eido got wind of the other member’s dissatisfaction with his communication, he skirted the issue in a follow-up letter, insisting it was a ‘misunderstanding.”

The final straw for George Zournas, after sticking by Eido through at least three major upheavals, was the revelation that Eido had been severely mistreating Soen Roshi. A stipend of $4000 had been promised to Soen to pay for his fare to the United States, his travels around the country, and as a donation to his temple in Japan. George learned that Soen had been given only half this amount, and worse still, that the money had been presented to him in dollar bills and filthy street money. In Japanese culture this is a contemptuous act, insulting and demoralizing. The money should have been presented in new, crisp, large bills, neatly packaged in rice paper. George was utterly disgusted.

Then there is the question of Eido’s mental health. Speaking as a physician, Dr. Tadao Ogura (栄道 老師), senior psychiatrist at the South Oaks Hospital in Long Island and long-time friend of Eido’s, had this to say in a letter to Peggy Crawford and George Zournas: “Eido is basically a weak man. The great energy that has enabled him to make such a splendid contribution at Dai Bosatsu and the New York Zendo has also been channeled into sexual energy. But this energy, he is completely unable to control. This, coupled with his lying, makes it essential that he be removed from Dai Bosatsu and the New York Zendo. Wherever he goes, he should never again be given a position of primary authority.”

But would Eido resign? As Frank Locicero explained at the time, “I have my doubts. Since his wife Aiho is a member of the board, and since of the remaining six, four-David Schnyer, Jean Bankier, Sylvan Busch and Lee Milton are under Eido’s control, it doesn’t look too promising.” A list was read of the grievances against Eido from the early 70’s to the present. David Schnyer’s response: “Well, raped anyone yet has he?”

Frank made a motion anyway, requesting that Eido amd Aiho be removed as chairman and treasurer of the Zen Studies Society, and that Eido be removed as abbot of Dai Bosatsu Zendo and the New York Zendo. The motion was seconded by Peggy Crawford.

It was denied, by a vote of four to three.

Eido Roshi remains Abbot of Dai Bosatsu Zendo and of New York Zendo, (although he has voluntarily resigned as chairman of the Zen Studies Society). His wife still holds the post of treasurer.

Frank Locicero, Peggy Crawford, Adam Fisher, and George Zournas have resigned from the society. A committee was to be formed immediately after the board meeting, under the leadership of Dr. Ogura (栄道 老師), to continue the investigation and suggesting a resolution, but apparently the society could not find three impartial members to serve upon it and the idea was abandoned.

I never received a “turning word” from Soen, who returned to Japan after his brief stay.

In November, Eido Roshi left for a visit to India and his native Japan. His journey was taken despite the fact that he would be absent for kessei, an intensive 90-day training period for serious Zen students. He has since returned to New York but is virtually in hiding and except for one brief appearance has not presented himself at the Catskill monastery or the New York Zendo.

One evening last fall, Eido Roshi returned to the city after leading a sesshin upstate to discover boldly painted across the door of the New York Zendo, the word “SHAME.” When he went home to his townhouse, he found the same message, “SHAME.”

| No member of the Zen community claims responsibility for the action. |

|

|